George Orwell’s arguably most famous novel, the dystopian Nineteen Eighty-Four, coined a number of phrases that are in widespread use today. One of them was “Big Brother,” an authority figure who watches every move you make, everywhere. The term has become synonymous with mass surveillance. As you can imagine, the book is easily as relevant today as it was back in 1949 when it was first published. (It’s a great read, btw.)

George Orwell’s arguably most famous novel, the dystopian Nineteen Eighty-Four, coined a number of phrases that are in widespread use today. One of them was “Big Brother,” an authority figure who watches every move you make, everywhere. The term has become synonymous with mass surveillance. As you can imagine, the book is easily as relevant today as it was back in 1949 when it was first published. (It’s a great read, btw.)

The usual complaints about modern-era Big Brothers – aside from that annoying reality show – tend to be targeted at initiatives to place more surveillance cameras in various locations (e.g. the camera-riddled London). Then of course there is the monitoring of our activities on the Internet by governments, ISPs and organizations with their own agendas.

Today, however, something completely different is happening, and surprisingly few red flags have been raised. We, the collective, are providing the raw surveillance data. We, not some dystopian state, are becoming the ones who monitor.

How is this happening? The key is your smartphone. Or perhaps we should say, your social use of your smartphone.

Rise of the collective Big Brother

You love your smartphone, right? You love having constant Internet access, your social apps always at hand, a camera, a video camera, and more, all in your pocket. And you use it a lot.

We’re getting used to a life increasingly under public scrutiny, and we’re getting used to sharing. Just a few years ago, none of us were sharing as much about ourselves, or others, as we are today. We, the collective social media user base, are building an enormous database of what is essentially a kind of surveillance data.

Capture from the film version of 1984, via Wikipedia.

Many of us keep taking photos and maybe even videos of friends, ourselves and locations we hang out in or visit. Then we upload them to Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and many other places.

Not only that, all this sharing often comes with attached location information and timestamps. This on top of the dedicated check-ins many do on Facebook and Foursquare. Then add the various tagging of pictures that is done on sites like Facebook (you know, tagging friends in photos).

Not all of us are doing this, but enough of us are. Collectively, we are providing the social networks with a wealth of information that can be accessed today via various public APIs. Pictures, videos, status updates, all with attached timestamps and location information.

We, the monitors

Although anyone with a bit of imagination can probably think up a dozen diabolical abuses of the data we provide to social networks, let’s take a couple of more mundane examples of things that are already happening.

For example, when you apply for a job, there is a good chance that your prospective employer will check you out online, search for pictures of you in various situations, see what people you hang with, etc. Companies have been doing this for years. Not all, but the practice is common enough.

Another example is simply a practical consideration. House burglars can see when you’re not at home if you share your location online. As many as 4 out of 5 do this already. One of the truly nasty side effects of location sharing.

Then there is the infamous Girls Around Me app, which was in creepy league of its own while it existed. The name pretty much speaks for itself.

The Girls Around Me app was yanked from the iOS app store, but there are still apps like Banjo, which also drags in location data from various social networks. People don’t even have to “check in” anywhere, they simply show up based on the location included in their latest status updates or pictures. This is not aggregated, anonymized data; actual individuals populate the app.

The Girls Around Me app was yanked from the iOS app store, but there are still apps like Banjo, which also drags in location data from various social networks. People don’t even have to “check in” anywhere, they simply show up based on the location included in their latest status updates or pictures. This is not aggregated, anonymized data; actual individuals populate the app.

There is a vast amount of collective “surveillance” data out there, and we keep adding to it. It is already technically possible to mine much of this shared data as a third party from various social networks via APIs. Apps like Banjo and Girls Like Me make this exceedingly clear.

Life in public is already changing our behavior

Here’s a very relevant anecdote of how our behavior is changing as a direct result of this collective surveillance.

Even if you’re not American you’ve probably heard about Spring Break, usually filled with wild partying, wet t-shirt contests, etc. Here’s the interesting the part: recently, these parties have started to calm down.

Why? Because now that everyone has a smartphone or at least a feature phone with a camera, you can’t go wild and not have it documented and uploaded to the Internet. College students are well aware of this, and don’t want to look bad.

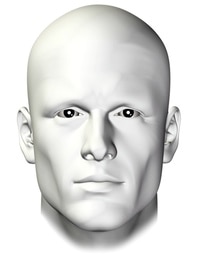

Facial recognition could take things to a new level

There’s also an elephant in the room, facial recognition. The technology already exists and is in limited use in various applications such as iPhoto, Picasa and even Facebook. Facial recognition applied broadly on social network data would open up a whole new can of worms.

There’s also an elephant in the room, facial recognition. The technology already exists and is in limited use in various applications such as iPhoto, Picasa and even Facebook. Facial recognition applied broadly on social network data would open up a whole new can of worms.

Here is a scenario: Imagine taking a picture in a restaurant or at a party, or even in the street. Now imagine facial recognition being applied to it, coupling everyone in the shot with a database of people. We could get a list of everyone in the shot, even people in the periphery who you don’t know or care about, people unaware they were having their picture taken.

Now imagine this being done routinely on all pictures on Facebook, where billions of photos are uploaded every month. Then combine it with the timestamps on these photos, and the location information.

Mind. Blown. At least it should be. You could track the activities of basically anyone this way, even if they don’t participate in social networks.

Oh, and then there’s voice recognition…

Conclusion

Privacy is an illusion these days. You don’t have to be a total privacy nut to see that. It also doesn’t take a genius to see that our collective information sharing is only increasing. An abundance of CCTV cameras aren’t necessary, we’re already monitoring ourselves. We provide the data, and many of us are already using it.

The question isn’t if someone will start abusing all this data, but when.

There’s a sticker on a radar screen in the movie Battleship which says, “In God We Trust, Everyone Else We Monitor.” It seemed appropriate to end with that.

Picture credits: Red Big Brother top picture and the Face via Shutterstock.