Mozilla’s development pace for Firefox went into overdrive this year, as they adopted a strategy similar to that which Google uses for the Chrome web browser. Mozilla’s new, rapid release schedule for Firefox calls for a new version every six weeks. On Tuesday, November 8, it’s already time for the release of Firefox 8.

Mozilla’s development pace for Firefox went into overdrive this year, as they adopted a strategy similar to that which Google uses for the Chrome web browser. Mozilla’s new, rapid release schedule for Firefox calls for a new version every six weeks. On Tuesday, November 8, it’s already time for the release of Firefox 8.

But there are clouds on the horizon. For every new version of Firefox that Mozilla releases, a fraction of users are for whatever reason not being upgraded. There’s a long tail of older versions starting to form, and over time this may accumulate enough version fragmentation that it could become a real problem.

To give you an example, Firefox 5 was the first version in this rapid release schedule and should be history by now, but it still clings on to almost 4% of the Firefox user base.

So imagine the effect of this kind of “left-behind” retention in the long run. Remember, at the current pace we’ll see at least eight new Firefox versions per year. Next November, the latest version will be Firefox 16.

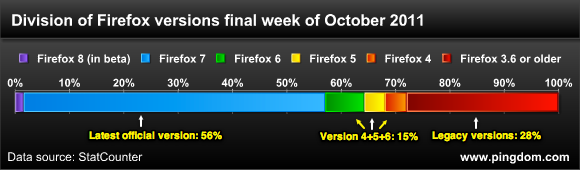

The current fragmentation of Firefox

Here’s the distribution of Firefox versions for the final week of October 2011, as measured by StatCounter. Note that this is at the later part of Firefox 7’s six-week cycle as the latest release version, so browser users should have had plenty of time to upgrade – or rather, be upgraded.

In case you’re wondering, the vast majority of the “3.6 or older” bracket is made up of version 3.6.

The good news is that the “legacy” versions of Firefox – those being version 3.6 or earlier – represent a rapidly diminishing portion. Early in June they accounted for 43% of all Firefox usage. Now, five months later, those older versions are down to representing “only” 28%. At the current rate of change, they will be down to around 8% in a year.

The bad news is that there is now a good-sized portion of users who are not following along from one version to the next in this new release schedule that Mozilla started with Firefox 5 in June.

Why is this happening?

It could possibly be an effect of the upgrade process not being automated effectively, or perhaps enterprise users are to blame. The typical reluctance of enterprises to upgrade software without ages of testing has been the bane of software progress for quite some time (part of the reason why IE 6 is still alive).

Perhaps those are both factors. We honestly don’t know. Firefox users do have the option to disable automatic updates, but they’re on by default. It’s hard imagining that many people opting out of upgrades.

A silver lining, the saving grace, the Good Thing

The saving grace in this whole situation is that at least the share of Firefox users running the very latest versions is not going to drop for a while. It might actually grow.

Why? Because people keep upgrading from older versions, like 3.6, filling up the gap that would otherwise be created. But once the pool of older Firefox versions starts to dry out, Mozilla could be in trouble.

Are we facing fragmentation hell?

As we mentioned in the introduction, with a new version coming every six weeks, we’re going to get eight new versions of Firefox every year (well, 8.7). If Firefox is going to leave behind a couple of percent of its users or so in every version update, things will quickly become messy even if those shares individually are rather small and will decrease over time.

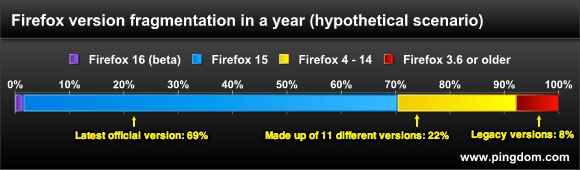

This is what things could possibly look like just one year from now, unless Mozilla comes up with a more effective upgrade process that doesn’t have users staying behind for every new version that arrives:

Now imagine web developers around the world collectively going bold from tearing their hair trying to test and support that many versions of Firefox. Then add another year on top of that, when we’ll be up to Firefox 24.

Final words

The bottom line is that leaving a chunk of the Firefox user base behind with each new version is not a sustainable situation in the long term, at least not with such a rapid release schedule.

It may well be that the good people at Mozilla already have some awesome plan in place to counter this trend, but if they don’t, it may be time to start thinking of one.